The paradox of dissociation

Sensory overload is a defining issue in autism, ADHD and other forms of neurodivergence, like high sensitivity. Sometimes, it shows up in obvious ways — like needing to wear sunglasses because sunlight is painful, or like being triggered into meltdown at a loud, unexpected noise.

Other times, the sensory overload is harder to discern. That doesn’t make it any less overwhelming, however. In fact, it can be these less observable sensory inputs that wreak the most havoc in a neurodivergent life.

What most people don’t recognize is that humans have more than five senses. In fact, the commonly-known senses of sight, sound, taste, touch and smell are really bundled into a single sense called exteroception. Add to it the interoceptive, proprioceptive, vestibular, cognitive and social senses, and you start to get a clearer picture of the potential for sensory overload on a second-by-second basis.

Before my official autism diagnosis, I was often thrown off by the concept of sensory overload because I actually love overwhelming my senses — I love bright colors, sunlight, big sounds and complex flavors. I’m also lucky enough to be synesthetic, meaning I regularly experience multiple senses from a single sensory input — I can taste the texture of music, for example.

I figured I couldn’t be autistic because my exteroception provides some of my favorite life experiences. And yet I resonated deeply with the autistic description of sensory overload. So I started paying attention to how it showed up. That’s how I arrived at my interoceptive overwhelm, and I’ve been on a mission to unpack it ever since.

Interoception is a broad sense that encompasses everything from hunger cues to the gut sense that something isn’t quite right about a situation. It is also the keeper of your emotions, from rage to contentment and beyond. It traverses your system through your Vagus Nerve, and it’s a bottom-up sense, meaning most of your interoceptive information flows up from your body to your brain and only rarely goes from your brain to your body.

It made perfect sense that I was regularly being flooded with sensations to the point of anxiety, physical pain, brain fog and occasional meltdowns. But it also conflicted with another fundamental self-understanding: I felt, as many autistics do, completely disconnected from my body.

How could I point to my interoceptive sense as the primary source of my sensory overwhelm and at the same time live so fully removed from it?

Turns out, the answer is pretty simple:

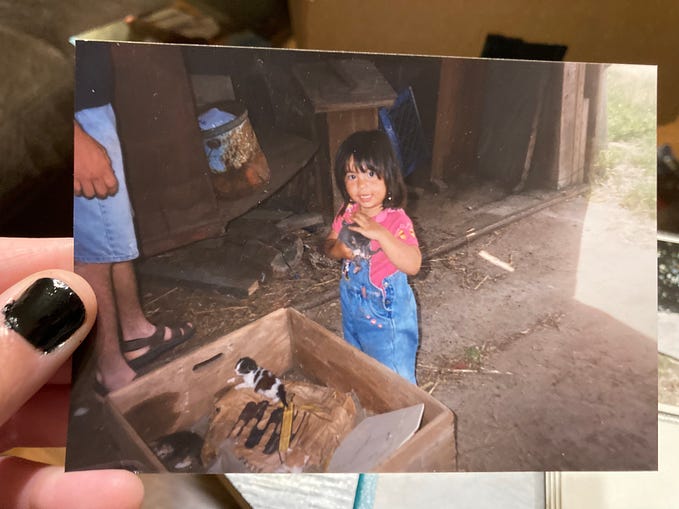

To survive under the immense weight of my interoception, I learned to dissociate at a young age.

I adapted by turning off, at a cognitive level, as much interoception as possible. Of course I couldn’t fully stop the sensations, but I could stop my ability to recognize, entertain or be influenced by them.

I wore my dissociation like sunglasses on a bright day. Thus I lived as a paradox: A highly tuned-in person with little capacity to recognize, let alone process, the sensations, emotions and urges bubbling up from my body.

The problem is this: Your body isn’t going to let you ignore it forever.

- When I didn’t respond to hunger or thirst as a child, my body gave me headaches as a way to stop me from burning fuel I didn’t have.

- Because I didn’t value relaxation, by my 30s, my body gave me chronic back pain, insomnia and muscle tension to slow me down.

And then, I had my breakdown at 38. That’s when I finally started to pay attention to what my body wants to tell me. But I was so late to the game. To suddenly start paying attention to unfamiliar sensations after nearly 40 years of dissociation sent me back developmentally to childhood when most people learn to recognize, process and manage their emotional state.

Now that I’ve learned applied neurology, I have a better idea about what’s going on, and that helps me be patient with myself as I grow neural pathways that never had a chance to fully develop.

- Interoceptive information flows up to the brain stem and limbic system — the oldest parts of our central nervous system — and unless it triggers a threat response, it is passed along to the insular cortex for processing.

- The back part of the insula receives a flood of interoceptive intel and passes it onto the central part of the insula for interpretation.

- If I had the right neural pathways in place, the central part would send along pertinent information to the front segment of insula to be used by the pre-frontal cortex (the thinking brain) to be properly modulated, assimilated or quieted.

- Instead, my interpretation center reads threat in either the content or volume of information and sends it back to the primitive parts of the brain, triggering a threat response — sometimes demanding dissociation and other times looping into a sense of shame that can quickly spiral into depression.

- (If you’ve ever wondered why you immediately feel depressed when your anxiety lifts, this could be the reason.)

One of the many things I love about applied neurology is how it can directly target the parts of the brain that need support.

In my case, to better activate the front of the insula so it can step in when the central interpretation starts to overflow, I use inhibition drills that strengthen the pre-frontal cortex’s influence over the insula — drills like the Stroop Test or N-Back Test — and this builds neural pathways that atrophied from years of dissociation, or never fully developed in the first place.

No, I am not curing my autism. Autism is a far more comprehensive experience than just a bit of underdeveloped insula. Instead, I’m creating the capacity to live less dissociated, and to not just tolerate my interoceptive overload but also to leverage it for wisdom, self-knowing and autonomy — for personal sovereignty.

The goal in applied neurology is to optimize the nervous system you were born with in service of your health and peak performance.

- Your circadian rhythm needs bright sunlight to optimize your energetic system — thus it is worth learning to live without wearing sunglasses as often.

- Sudden noises are going to happen in life — thus it is worth learning to calm the nervous system on-command and mitigate the risk of noise-triggered meltdowns.

- And the information from your body is key to your health, safety and self-worth — thus it is worth building the neuro-pathways that make dissociation less necessary.

The moral of the story? Your high sensory nature — your sensory overwhelm in whatever flavor it shows up — is a function of your unique brain. And you can learn to harness it.

- I get more information interoceptively than the average person. What inner wisdoms are possible for me as I learn how to handle the flood without it shutting me down?

- You might get more information from light, sound, taste, touch or any other sense. What’s possible for you when you learn to work with the nuances of your own brain and nervous system?

It’s my mission to help you find out because you were born high sensory for a reason. That’s a fact.

Want to know more about your brain? Book a free discovery call. We can talk about sensory overload, pain signals, emotional processing and so much more. Once you know more about what’s going on inside, you have the capacity to leverage it for your advantage.